The following was written by Lynette (nee) Lewis about her memories of Indented Head. Lynette was called Nett or Netty by her friends.

Parents

When my parents, Herbert Hague Lewis and Alice Elizabeth Congdon married in 1916, they lived in Belmont, Geelong.

My mother's mother, Emma Mallett, was born in Geelong and married George Congdon, an architect-builder from "Lydford", England in 1890. They had two sons and one daughter Alice Elizabeth, born 13th July 1891.

My father's parents, William and Mary Lewis came from Yorkshire, and settled on a small mixed farm and orchard in Grovedale, known then as German Town. They had four daughters and one son, Herbert, born in 1889, the eldest of the children.

My father, who was good at Mathematics wanted to go further than Grovedale Primary School, so he walked to Flinders School in Geelong. Sometimes, if the punt was not handy, he would strip off, and tread water across the Barwon, carrying his clothes on his head, so that he would not be late. Because he was short, only 5'2", he was unable to get a job as Driver of Signalman on the Railways, so he took many jobs, such as a ganger, at the Harbor Trust, planting trees in the new State town of Wonthaggi in 1910, and helping on the family farm.

My mother was a milliner by trade, but had to stop work when married.

Indented Head

They lived for 4 years in Belmont, during which time my father worked in Thorne's Sport Store stringing tennis-racquets. I was born there on 19th December 1918 and because my father's health was affected by indoor work, in 1920, they bought a 40 acre farm at Indented Head, from Albert Johnson. It ran between the Esplanade, McDonald Street and Ibbotson Street.

The weatherboard house was small, four rooms off a central passage, a wood-stove and pantry were the only amenities. My mother bucketed water from a tank into an outside copper and washed by hand in troughs set under lucerne trees, at the side of the house. It must have been a hard and lonely time for my mother, who had been town bred, with comfortable living conditions.

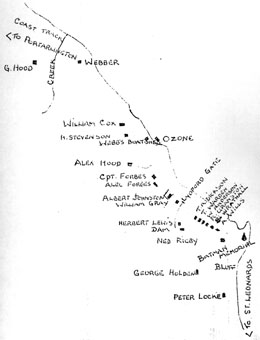

Residents in 1920

The residents of Indented Head in 1920 were :-

- What is now "Blue Waters Estate" was Webbers Farm, with the house, surrounded by hardy boobialla trees, on the road that hugged the beach and went through the salt marsh where houses now stand. Although Webber was a hard working man, the farm was poor. He left during the depression. He had one daughter at that time.

- Will Cox had the next farm (now Paradise Park) with large cypress trees marking the drive. He had a large family : Adelyn, Phyllis, Susie, Jean and Billy, Jean being the same age as myself. They were a friendly, Catholic family, who also left in the depression, selling out to Elliott Cairns.

- Harry Stevenson, a bachelor, lived in a two roomed hut under a gum-tree just off the corner of the Esplanade and Batman Street, on part of Hood's property. He had a big brown retriever dog that would bring his paper, pipe and slippers for him. He liked to talk about literature to my mother, and he gave me a copy of the first edition of "The Sentimental Bloke" by C. J. Dennis, inscribed "From Ole Harry Stevo".

- Alex Hood was next, and his house was built well back from the road on a gentle rise that overlooked his large property. He always rode a fine horse and was considered by the rest of us as well-to-do gentry.

- Captain Forbes lived in what is now "Lazy Days", a weatherboard house, notable for port-hole windows in front, and the saloon and red plush seats each side of his front door, which had once graced the steam-ship 'Edina'. Also from the 'Edina', of which he was captain, was the figure-head, which stood on a wooden pedestal in the front garden, near a huge Moreton-Bay Fig tree.

- Alex Forbes, the captain's brother, lived next door in the cabins from the 'Edina', a long narrow building with small windows. He was a quiet bachelor, who often sat on his front step to smoke his pipe. He and Stevo had flat bottomed boats they rowed out to fish. These they kept under the cliff near Webb's boatshed, now No 7.

- Albert Johnson was next, now No. 326, on a block taken out of the farm. He was a fisherman, who was very hard of hearing. His wife was a slightly built Moari woman, who spent her leisure in her colourful garden.

- Our farm was name "Lydford" after my mother's father's home town in England. Our front gate was where Lewis Street now joins the Esplanade, and the track, which was lined with lucerne, ran back to the house which was near the back lane, now McDonald Street.

- Next was Ned Ribgy, fisherman-farmer, who lived opposite Batman Memorial, No. 358, and his farm extended from McDonald Street to Ibbotson Street and bordered George Holden's property. He also stripped wattle bark for tanning.

- On the sand hill facing the bluff, was George Holden's property, a small farm that ran down to the Salt Lake. George belonged to the Holdens of Circus fame. He was a Salvation Army man, but he attended the St. Leonard's Church of England as it was the only church in the district.

- On the flat, between the road and the lake, was the little home of Peter Locke, fisherman. Strictly speaking, he was not in Indented Heads, but he was close enough to be a neighbour. He was a tall handsome man, with a small wife, who spent her time in the absorbing hobby of shellcraft. Her sitting-room and verandah was crowded with little houses and trinket boxes of all shapes and sizes, that she had created from shells she gathered on the beach. We still have several that my mother bought, made on cigar boxes.

|

|

Early Memories

My first memory, when little more than two, was of being wrapped in blankets and placed in a wooden capstan chair outside the kitchen-door on some asphalt, while my mother and father fought a fire in the wattle paddock, east of the house. The blaze, which was thought to have been started by a careless swagman, brought neighbours from St. Leonards and around to help. My mother kept running to the tank to wet a bag to belt out the sparks in the dry grass next to the house, while the men fought the blaze.

Times were hard, the district poor, but the people helped others in trouble without expecting reward.

My father was continually harassed by Albert Johnson, better known as "Squeaker" because of his high pitched voice. He would come across to where Dad was working, tell him he was doing it the wrong way, or threaten him with fines or police action. The incidents I remember of the early days were :

One evening, when my mother was washing the dishes in a dish on the kitchen table, my father was sitting under a small window near the stove, when he motioned my mother to be quiet. He then picked up the dish-water, sneaked out the door and heaved the water along the wall of the house. There was a scuffling noise in the bushes, then my father returned laughing. He had known Squeaker was eavesdropping because he had taunted him with things Dad knew he had only told my mother.

Another time, our dog had a pup, and when it was about 4 months old, the Dog Inspector called, so, to save a trip of 5 miles to Portarlington to register it at 6 months old, Dad paid the license. Soon after, the police arrived and asked Dad to show his license. He did so. The policeman apologized and said it had been reported so he was obliged to investigate. When the policeman told Johnson that the pup was licensed, Johnson said it shouldn't have been because it wasn't 6 months old.

Johnson would complain, if our bull was loose, that it ruined his fence, and when it was tethered, he threatened to report it for cruelty to animals. When my father didn't want the bull with the cows, after milking in the morning, he would lead it by a chain through a ring in the nose, to where the grass was thick, and bring it in to the home paddock after milking at night. One day, when Dad was leading the bull to good grass not far from Johnson's house, just as he was about to hammer in the stake, the saw Johnson coming towards him, shouting and gesticulating. My father pretended not to see him, but waited until he was quite close, then with a shout Dad let go of the bull. With a bellow it leaped, and so did Johnson, who didn't stop running till he vaulted over the cement wall that fenced his back-yard vegetable garden. I think this episode may have ended his direct interference.

It was about this time, that a St. Leonard's man, Len Corrigan, began courting Johnson's daughter, Ruby. He was a fine type of man and approached the parents to speak of his intentions. Squeaker didn't wait to hear but threatened him with a rifle, and ordered him never to set foot there again, nor come near his daughter. The couple were broken-hearted, but not beaten. It was arranged that, when Squeaker was well away fishing, Ruby would come to our place and wait for Len, who made his way up the back lane that was thick with Melaleukas at that time. Mrs. Johnson would keep nit [act as sentinel] as she worked in her flower garden, and when Squeaker turned for home, she would run through our wattle paddock and call to Mum, who would then rush to the lane and 'coo-ee' to the lovers. By the time Squeaker sailed in, his wife was on the beach to help him pull up the boat, and Ruby was busy at home. Eventually, they eloped and became good, respected citizens of St. Leonards, keeping the Post Office which was on the cliff-top opposite Ibbotson Street.

Poverty

During these early days, my father often sat with his head in his hands steeped in despair. He had worked hard growing a beautiful crop of carrots, and after digging them by hand and carting them to Portarlington to the 'Edina' for the Melbourne market, he received back a bill for market fees. He ploughed them up and fed them to the pigs. There was no money, but my parents exchanged for goods their farm products, as many district people did, so we had food at least.

An Indian hawker, who used to spend the night at our place, exchanged cloth for poultry and hay for his horse and insisted on cooking his own meal over an open fire. He then slept in his van, rising very early in the morning to continue his trade.

Swaggies would camp in the Melaleukas in the back lane near our dam, often putting in a day's work for a meal and tucker to take away. I remember one old chap, who came regularly because Mum was kind to him, picked up an old saucepan I had in my play-house, brushed it off on his pants, and much to my disgust, put it in his swag.

It was a great day of bustle and excitement when the pigs were ready for bacon. Day, the butcher, would arrive in a trap and assemble his tools while Dad got ready a tub and plenty of boiling water in the copper. The pig would be stabbed and plunged squealing into the tub where its bristles would be rubbed off, then Day would cut it up, leaving some for my parents to cure. My father would make the brine in a barrel and then, each night, he would bring it onto the kitchen table, and rub brown sugar into it. The night he declared it ready, Mum would put on the pan and we would have a delicious supper of bacon and eggs.

When our sow had more piglets than she had tits, my mother would feed them from a bottle, with extra tit-bits for the runt who invariably missed out. The piglets got to know her and would clamour and squeal when they saw her coming. One afternoon, Mum dressed and set off down the lane to visit Rigby's. To her embarrassment, 13 piglets set off behind her and refused to go home, until she returned with them and locked them up.

Another time, just on dusk, a terrible banging came from the back door, and my mother and I started in fear. Mum opened the dining-room door cautiously and then burst out laughing - Daisy, the scavenger of our cow-herd, was standing in the kitchen doorway with a bucket caught around her horns. She had come to the house knowing my mother kept green scraps for the chooks near the door.

Tornado

It was about 1924, when I was about six years old, that Dad had just finished work and Mum had lit the kerosene0lamp, when a strange rumbling noise began. It got louder and louder, until the house shook, dishes on the dresser rattled and Dad had to hold the lamp while this terrific wind roared around us. It was soon over. My father took the lantern and we went outside into an eerie quiet.

The big tree, where the chooks roosted, was split in half, and deposited a chain away onto the wood-heap with the chooks still in it. The roof of the pig-sty was twisted and scattered yards away over the paddock and when we walked to the road, we found a swather of ti-tree had been ripped out along the foreshore. The roof of the "umbrella-house" (No. 336) which T. A. Dickson was having built, was lifted holus-bolus off the bolts and was hanging partly on one wall and partly on a big Casuarina (she-oak).

Boatsheds

One of the first boatsheds at Indented Head, which nestled among ti-trees and boobiallas, under the cliff near the Ozone, was Webbs. When they were holidaying there, they would invite all who would, to an old time dance, and I can remember my parents taking me to the boat-shed full of dancing, laughing people. When the fiddler stopped, some dancers would walk out onto the beach to cool off. I waited for the supper, when loads of good things to eat would be carried around on trays. After the 1940-45 war, the Foreshore Committee ruled that no one shall live in the boatsheds.

Transport

Transport was by horse and cart or by Pigdon's van - a T-model Ford van with a ½ door at the back, an iron step and leather seats along each side. My mother and I would ride in Pigdon's van when we went by 'Edina' to Melbourne, sitting among boxes of fish and parcels, also being sent to Melbourne to the market. Our last trip on the 'Edina' was a memorable one. Usually May Miller, of Portarlington, used to play the piano in the saloon, but this day it was so rough, the piano and seats were sliding about, the sailors were carrying buckets of sand for sea-sick people, and lashing the seats down. My mother took me up on deck into the wind. The Captain motioned us up onto the bridge where he was struggling with the wheel, and we stood there with our faces turned to the fresh wind and we were among the very few not sea-sick.

The 'Edina' used to bring the Trades Picnics to Portarlington when I went to school there. By the afternoon, drunks would be hanging over the school fence talking to us, or sleeping it off in "Little Reserve". When the 'Edina' blew her horn to warn them to embark for home, they would stagger and fall out of the windows and doors of the Grand Hotel and stagger down the hill to the pier, much to the kids' amusement.

One time, a woman in an expensive fur coat arrived on the pier just as the gang-plank was hauled in; she staggered to the side and before anyone could stop her, jumped. Her coat flew out around her as she landed in the water between the boat and the pier, and was eventually hauled out, a sorry, dripping sight.

My mother became ill, so my father, who was very worried, sought help from Mrs. Holden, who had been a nurse. She came and helped prepare Mum for the journey to Geelong, by hose and jinker, to attend a doctor. Dr. Mary De Garris, the only lade doctor at that time, came to my aunt's house to attend her. As Mum had to remain there for some weeks, my father came in to se her by the carrier, Dummy Hood, who lived at St. Leonards on the old St. Leonards - Portarlington Road. It was said, when he was a child he contracted measles, and sneaked outside in the cold to play. This caused him to be both deaf and dumb. His wife was also deaf and dumb, but his daughter, Sybil, who went to St. Leonards school was not affected.

Dad and I were returning home with Dummy in his old T-model Ford van and it is a journey I will always remember. As we drove out of Geelong, Dummy rested a note-pad on the steering-wheel to write a note to my father, disregarding the traffic. The tram-driver frantically rang his bell as he watched us approach - just in time Dummy wrenched the wheel, missed the tram, then casually went on writing. As we chugged up the 7-Mile Hill, there was a crash and the van started backwards. Dummy jumped out and running alongside, threw a chock under the wheel to stop it, and then pointed. Lying on the road was the engine. Dad got out to help him put it back. Dummy then advanced the spark on the steering-wheel, cranked the engine, and away she went; Dummy jumped aboard, released the hand-brake and we were off. Soon the engine began to boil, and as there was no radiator-cap, the hot water splashed through the top half of the windscreen which wasn't there either. Dad put his coat over me until we thankfully reached home.

Holden Family

When I became ill, my father once more went for Mrs. Holden. She walked across Rigby's farm to our house, and after having a good look, declared it was scarlet fever. She came often to relieve Mum who was exhausted with work and worry, and her kindness in our need formed the basis of a good friendship. I loved to visit the Holdens'. From the moment you reached the gate, their pet cockatoo would shout "Hello! Shut the gate! Mum! Mum! They come!" and by the time you reached the house, the Holdens would be out smiling a welcome. Cocky would then do his tricks - "Does Cocky want a drink?" and the bird would perch on Mrs. Holden's shoulder, and putting his beak down her dress, make sucking noises.

George would always have something he was making or writing. he would play a violin he made from a tea chest, or play a saw with a bow he made, or he would take you to his den. This was a room, with one window, built on top of a dray wheel, and as the sun moved across the sky, George would turn the wheel to catch the sun in his window. The very first solar-heating.

He had his library of favourite books and he would read or compose poetry. Once he showed us a map in water-colours he had drawn of old St. Leonards, showing his parents home, when the Aborigines came for their flour and he played with the piccaninnies; the old Coffee Palace and the oak-ship anchored off the pier that was a restaurant. He often came to our house to talk of books with my mother, and to me, when I studied English at Geelong High School.

Ozone

When I was six, in 1925, my parents took me to the beach one calm mild evening to watch the Ozone being towed in to Indented Head. The Geelong Yacht Club was interested in using her as a breakwater and commissioned Cpt. Forbes to bring her from Port Melbourne, then experts would indicate the correct position to settle her.

It was a beautiful sight, watching the Ozone, fully outlined in lights, slowly coming towards us, and there was excitement in the crowd, After it was anchored, Cpt. Forbes rowed to shore in a small boat and on to his house where a merry celebration party continued into the small hours. Suddenly, a storm blew up and the Ozone began to drag anchor. The Captain, well under the weather himself, panicked. He rowed out, scrambled aboard and opened up the sea-cocks, letting her down where she was. What a row when the experts arrived in the morning to find the paddle-steamer too near the shore. It wasn't long before the Ozone sanded up and was useless except for anglers and children to play on.

For years, we children climbed the paddles, chased around the gunnels, and dived into the engine-well, imagining exciting pirate raids and battles at sea.

Stanley Family

At this time too, family friends, Charlie and Millie Stanley, with their five children, would spend a holiday with us, arriving in a horse-drawn cart. Dad, a short plum Englishman in a dark suit, stiff collar and bowler hat in the driver's seat, and Mum, even plumper and shorter, in a black dress and hat, with Lena the baby on her knee, sat beside him in front, while the four sons sat behind. I looked forward to them coming because they brought cream biscuits, a real luxury, from their grocer's shop in Geelong, and much fun and bustle. Charlie would breathe deeply and say "I'll take a walk upon your meadow, Herbert!" with pomp and a strong Yorkshire accent. My mother and Millie talked in the kitchen, while they prepared endless meals, and as an only girl among four boys, I did my best to keep up to tree-climbing, sliding down the sides of the dam on sheets of tin, and building cubby houses. I must have succeeded, because my mother insisted that I wear blue dungarees and boots.

School

In 1925, as I had turned six, my mother arranged that I should go to school with the Cox children, at St. Leonards, which was a one-teacher school. Addie and Phyllis rode one horse while I was to fit on old Possum, a Shetland of considerable cunning, with Susie and Jean. Possum stood still while we all climbed the gate-post and onto his back, then moved off briskly before Susie could gather the reins, passing under the lowest branch he could find and sweeping us all off his back. All I can remember of those schooldays, was standing around an elderly, plumpish man, who sat in a wooden capstan-chair, hearing us read in turn from the "Primer". Some of the names I remember are Cox, Rigby, Pigdon, Martinson, Hood, Locke, Belfrage and Trewin.

During the year, my mother was ill in Geelong, so I attended South Geelong Primary for some months, by which time, St. Leonard's closed as there were not enough pupils.

The following year, as Mum thought I was too young to go to Portarlington, five miles away, I went to stay with my grandparents at Grovedale, and for twelve months I attended the Grovedale State School. I'm afraid my memory of lessons is nil, but I still have a vivid memory of the lady teacher's jazz-garters. Each day we would wait in anticipation of her reaching upwards, and each time we would be rewarded by garters with ribbons, cupie-dolls, or sprays of flowers in gorgeous colours, worn just below the knee.

My best friend was Charlie Klempke, also an only child. His aunt would lift a little hatch, pass out our afternoon tea, then we would take it to the top of a huge pine-tree where Charlie had built a very passable cubby. Towards the end of the year, my parents bought a Chevrolet car. Mum went into Geelong, bought the car and was given about ½ hour instruction at the garage, then onto the police for her license. The old Irish policeman at South Geelong just asked her where she drove from and then handed her the license. After a few years, she ran a hire-car service from Indented Head to Geelong each Thursday.

By this time, the Cox children drove a jinker to Portarlington school, so Mum asked if I could go with them. Phyllis, Susie and Jean sat on the seat, and I sat on the floor with my feet out on the step. One morning we were just on the coast road near Webber's farm when the leather holding the shaft broke, throwing all the weight onto one side. Possum took fright and began running in circles. The girls screamed, making the pony go faster and soon the wheel caught on a fence-post, tipping us upside down. I was thrown through the spokes of the wheel, but fortunately, the harness broke altogether and the pony bolted towards home. Mr. Webber, who was working in the paddock, brought his dray across, and after lifting us in, drove us to Coxs'. Phyllis and Jean were bruised and shaken, Susie was concussed, and I was badly bruised around the hips. As the jinker was smashed, my father bought a four-wheel wagonette and a black pony called Dolly, who had been trained as a children's pony, so our next conveyance had more room. I used to stable the pony at Charlie Cox's place in Portarlington, about ¼ mile from the school. The Cox family left the district shortly after this, so I took Edna and Gordon Hood, children of George Hood, who lived about a kilometre out of Indented Head on the Portarlington Road.

One day, as I was returning from school, Dolly pricked up her ears and began to quiver. Coming towards us was an old car with no tyres driven by Mr. Plish (Cpt. Forbes son-in-law). The iron rims were bumping and clanging on the rough gravel road with so much noise. Dolly bolted in fright. I hung onto the reins with all my might, trying to avoid the trees, but the pony galloped full tilt, with the wagonette lurching and bumping. My father hear the noise and ran out onto the road calling to the pony, then caught the bridle. Dolly slowed down, still trembling and sweating - and so was I.

Driving five miles twice a day became very boring, so we used to think of diversions. In the Spring, when the grass was green, we would tie the reins to the dash-board, hope of the back, and slide, holding onto the back-tray. Sometimes, if we were too heavy, Dolly would stop altogether and refuse to move until we got into the wagonette. We often sneaked up back roads to bandicoot turnips or carrots, or raid a fruit tree that hung over a fence.

After the Hoods left school, I rode to school on my own. One hot day, when riding Dolly home, I felt tired and lay back with my head on Dolly's rump. I must have slept, because when I sat up with a start, to my amazement, Dolly had gathered up all of Tom Calhoun's cows and was calmly walking behind a long line headed for the beach road along Webber's farm. I pulled Dolly off the track, dug my heels into her flanks and galloped off, leaving the cows and Tom to work that one out.

Illness

The worst experience I had riding to school was during one winter when we had a lot of rain and the creek was flooded as it crossed the road across Webber's farm. Dolly swam across, but I was wet through and sat all day feeling cold. The next morning, when I tried to get out of bed, my legs gave way under me and I collapsed onto the floor. My mother was terrified that I had contracted Polio which was prevalent then and incurable at that time. After travelling to Geelong to Dr. Mary De Garris, we were relieved to find it was muscular rheumatism, and, although painful, would pass off in 5-6 weeks. My grandmother, who had soothing hands and endless patience, massaged my legs for hours while I read Oliver Twist, David Copperfield and Little Dorritt to pass the time.

Church

Before my parents bought the National Chev, my mother used to either drive to Church at St. Leonards by jinker and pony or, if the service was in the evening, Rev. Leuwin would have a meal with us and then drive my mother to Church in his jinker. No matter how Mum or the Minister pleaded, my father wouldn't go to Church, always claiming he had too much work. However, one Sunday, Leuwin offered to help Dad with the chores so he could go to Church. This involved cutting a load of maize, then feeding it through the chaff-cutter by hand. Rev. Leuwin chose to turn the handle while my father fed the maize into the machine. Leuwin started in fine style. Dad kept stuffing the maize in greater amounts until Leuwin was sweating. he took off his jacket and resolutely started again, remarking it was harder than he thought. Dad said nothing; just fed in more maize until the Reverend, puffing and panting, had to give in. Dad then saw both of them off to Church, then returned to the shed only to find he had jammed the maize so hard he couldn't turn it either, and dark was well upon him before he got it free. My mother, who had a fair idea what had happened, could only say "Oh Herbert!".

When Church was held in the afternoon, my mother took me,. Rev. Leuwin was an Englishman who had been educated traditionally and had no understanding of Australian conditions and especially country life. His sermons were in language and content quite distant from his congregation and it was only his mannerisms that kept them awake. When he began preaching, he would move sideways, giving a little kick with one leg until he reached the organ, then he would start back on the other leg. We children would sit near the back, waiting on Mrs. Stent from the lolly shop, who was always late. She would sidle into the back seat, sharing out her aniseed balls and sharing our jokes, such as when George Holden would fall asleep, then wake when the hymn started, coming in a bar behind and out of tune, or when the two Miss Gunns, very weighty spinsters who visited the Andersons, stuck to the freshly varnished seats and rose with a ri-i-ipping sound as their dresses pulled free.

One Sunday, my straw-hat was hurting my ears, so my mother took it off. As we filed out of church, Rev. Leuwin chastised me for having no hat on in church. Mum came to my rescue asking "Why have women long hair?" That finished the church going for a long time, to my relief. My mother was a kind generous woman who would always do a good turn, a real Christian at heart, who had a genuine religious belief and lived by it. When she decided that the church was not concerned about the people in a loving way, but obsessed with its own ritual, I felt proud of her and her integrity.

Holiday Houses Built

About the middle 1920s, the well-to-do, mostly from Geelong, began to buy land at Indented Head, and build holiday homes along the Esplanade, east of Lewis Street. It was the building of these houses that gave my parents an income other than the farm. My father did cement work, carting the sand by dray from our sand hill, now a pine plantation, mixing the cement by shovel on a sheet of plain iron, and barrowing it to the moulds. My mother boarded the tradesmen, up to eight at a time, cooking all the meals herself and serving them at our big dining-table, complete with white tablecloth. Some of the men said it was better than home, and one was so appreciative, he designed and built a tapestry brick fire-place representing the rising sun, in our lounge. It was a beautiful piece of art, but it needed a much larger room to set it off. Mum also sold milk, cream and butter to visitors. The money they earned was little enough reward for the hard work that they both put in.

Dickson Family

Mr. T. A. Dickson, a chemist from Geelong, was the first to build the "umbrella house", so named because of the shape of the roof, which is now No. 336. he made money and fame out of a tonic called "Great Heads", "Always fit for a game with the kids", featuring an old man playing cricket with the boys on the label. Miss Everard, his wife's relation, who stayed there for a holiday, wrote a story for the "Australian Journal" of 1926, on Indented Head and featured my mother as the "cow-like woman", and my father as a "mollusc strapped into trousers". She was no more flattering about other personalities which didn't please us after being neighbourly to them.

After his first wife died, Dickson married a younger woman, who became friends with us and the numerous possums that sat on her verandah roof to be fed.

Dickson sold his chemist business and bought a farm at Claire in South Australia, where he lost most of his fortune.

Warden Family

Next, at "Dalhousie", was Thomas Warden, manager of the old Victoria Hotel in Geelong, a tight-fisted Scot. Each year, he used to give his son Ramsay and daughter Muriel a holiday for about 6 weeks. There would be about twenty young people staying there, with a housekeeper to cook and clean. Each night they would hold dances and parties into the early hours, then sleep most of the day, sunbaking in the nude on the roof. The house-keeper was so upset at the extravagance and waste of food, she came across to us and asked if we could use it. Each day, Dad would call in with the dray and cart off cases of stone fruit, sponges with only a slice eaten, bread and meat. Some my mother used, but our pigs lived very well indeed. We too were appalled at the waste during a period of so much poverty. We especially were dismayed, because my father, who did the cement work on Warden's house, mixing it by hand, lifting it up in buckets where it had to be rammed, and working for eight hours a day at 1/- per hour, would have to wait to be paid. When he presented his bill, Warden would beat him down to 9d or dispute the hours worked. Although my father worked on most of the houses, Warden was the only one who disputed the accounts.

Wrathall Family

Steve Wrathall, a landlord from Geelong, who had made his money selling water to the Kalgoorlie miners, was one of the first to build a holiday house. He always had a grand scheme going. One such scheme was the growing of Passiflora. He brought a lad of 14 from the Orphanage to watch the house and attend the vines planted in the paddock behind the house. He would return to Geelong, leaving the boy alone to fend for himself. Dad found the boy crying in fear and loneliness one night, so my Mother took care of him during the periods that Wrathall was absent. Eventually, the Welfare Officer called to check and found the boy alone, so the boy was taken away. Although Wrathall expected the boy to stay alone, he was too afraid to walk home at night after visiting us, and my father had to walk with him and see him safely into the house.

Sometimes he would invite us for the evening, to listen to his gramophone and records of Dame Clara Butt, Nellie Melba and Peter Dawson. It was a much more sophisticated machine than our old "Edison" with the cylindrical records with such gems as Horrie Ford singing "The Fisherman's Daughter".

About this time Wrathall became very interested in Spiritualism which was having a popular run. He was so enthused, he thought we would fall for the benefits of Spiritualism also, and arranged for an evening when he would introduce us to this amazing lady Medium who had actually been in touch with his head son. The night arrived; we all sat around the table touching each other's fingers, the light was blown out, and we were to listen and the spirits would contact us. An eerie tap-tap-tap broke the silence - but the spirits didn't come. Wrathall went home convinced, but maybe the Medium wondered a bit. When they had gone, my father showed us how he had contrived the "tap", under the table, so we had a good laugh after all.

One thing Wrathall did achieve was the forming of the Batman Park Foreshore Committee to manage the foreshore. He planted many exotic trees popular at the time, from Dicksons property to the "Day Picnic Area". Many of the exotics, including the golden cyprus died, but the green cyprus grew in the shelter of the ti-tree. Once it established, it killed out the native vegetation, and now forms a dense cover which gives shade on a hot day, but is dark and draughty most of the time, not a sea-side tree.

The Batman Park Committee made many rules, some of them in their own interests, such as :- the residents with property along the Esplanade could build a boat-shed on the beach in certain places, but not in front of their properties as that was "Reserve".

When my father asked to build a shed in front of his property, he was refused, until he took it to the Committee and pointed out that he owned more property than they did, and they had their sheds built in front of his farmland, so they had to relent and Dad built his shed, No. 19 and later No. 20, using beach-sand with the cement. Ironically, he also had done the cement work on the sheds of Anderson, Warden, Wrathall, Wills and Backwell, most of whom were on the Committee.

Wrathall then thought of Batman's 100th anniversary landing at Indented Head to put us on the map. My father was asked to build the monument, so Mr. Harding of Portarlington carted the stone from the point, and my father fashioned them and built the monument. He also built the stone and cement seat, which we laughingly called Batman's tomb. A great crowd gathered on that day in 1935 to commemorate the landing; on this occasion my father heated the "hot dogs" in a copper for the luncheon.

Steve Wrathall's daughter, Ethel, used to visit my mother when she sometimes came with him after the mother died. She was like many of her generation :- the boyfriend killed in World War 1 and she was left to look after a mother, restricted by Edwardian convention. Ethel married Taylor, a building contractor, late in life, and they built a house at No. 357 the Esplanade.

Anderson Family

Mr. W. Anderson built "Te Whare" next to "Dalhousie", and his wife and only daughter, Marcia, used to spend the summer there. They also had a housekeeper, and many friends to stay. As children, I can remember sneaking through the ti-tree spying on Marcia and her fiance, Bert Rooke (hardware and gift store in Ryrie Street, Geelong) while they were courting. When they caught us, they would speak to us pleasantly and we would feel rather ashamed of ourselves doing such a thing to such nice people. Bert Rooke was a kind, gentle soul, who spent much of his time and money working for the Blind Guide Dog Association and would have dearly loved my husband, Joe, to have a dog.

NOTE ADDED BY THE EDITOR January 2021: We have been contacted by Janey Lewis, the great grand daughter of William Robert Anderson who said that the details provided by Lynette Lewis were incorrect. In fairness to Lynette, she has commented on people that she remembered in the 1920s, and when you read the information provided by Janey, both Janey and Lynette were correct. Janey's additions to the Anderson family:

William had 4 daughters - 3 daughters by his first wife - Enid, Leila and Dorothy. William's first wife died and he remarried Gertrude and had one daughter - apparently her nae was Mercia and not Marcia - but William and Gertrude did only have one daughter as stated by Lynette.

Cranstoun Family

Robert Cranstoun, a traveller for Swallow & Ariel Biscuits, built Batman Lodge. We got to know he and his wife very well, for as soon as they arrived of a week-end, she would visit my mother and tell us about the concerts and happenings in Geelong. She and Mum were both interested in many similar things and Mrs. Cranstoun loved company. She would organize evenings for us children, the Grays, Duffields, Wills and myself which were great fun. We played all sorts of parlour games followed by a grand supper. I think she made up for not having a child of her own. They owned a beautiful red-setter dog, and it became a familiar sight to see the red-setter travelling on the running-board of the car with its front paws on the mud-guard and its big ears flying in the wind.

Wills Family

Bert Wills was from Colac, where he conducted a Newsagency. His brother had one of the earliest radio shops, and when he came to stay with Bert and Minnie, we were invited for the evening to hear the marvels of the "wireless" as it was then called. What a difference from our "crystal" set! he talked my father into buying it, so we were one of the first in Indented Head to have a set. It was a polished-wooden case, with 5-6 batteries of varying sizes, and an indoor aerial on the lid. It also had a large speaker on a trailing cord that Mum and I would take into the bedroom to listen in bed, where it was warmer than by the kitchen fire.

The novelty brought many visitors to our house, including Cpt. Forbes. He used to come to listen to the cricket, which was relayed from 3DB, by Charlie Vaude. The scores would be called from London, then Charlie would make up a description of play with appropriate sounds and in between, he would tell jokes, stories and sketches until play stopped in the small hours of the morning. The Captain would arrive complete with walking stick, a woollen scarf around his neck, a dirty pullover and trousers rather frayed, and his toe poking out of his sandshoes. He used to chew his tobacco and the dottle would run down his chin and under his scarf. As a child I used to sit fascinated, waiting for it to dribble out from the hole in his sandshoe.

Gault

Gault, who bought the land west of Ozone Street, was a flock manufacturer in Brunswick. As his wife had left him, he used to have an elderly couple, the wife to cook and the husband to caretake the property and citrus orchard. Fred Herbstreet and his wife were the first I remember. She was a plump, friendly lady, and Fred was too. He became well known, especially by the Mailman, who always knew which way Fred had taken off in his car by the tools dropped along the road. Fred was always in a hurry, and when he set off for a message, the tools dropping off his car as he went, he would wave and shout, "She's right! I'll get 'em on the way back".

Gault's next caretakers were the Nugents. Mrs. Nugent was a happy women who loved a game of cards. As they had no car, they would come to the dance and Euchre in the St. Leonard's Hall, with my parents, and when we arrived home again, she would insist on us coming in for more cards. There would be a fine supper ready, then cards would be played until the small hours. Her grand-daughter, Dorothy Hayes, had a nervous break-down and came to live with her grandparents. We became firm friends and Dorothy used to stay with us after her grandparents left Indented Head.

Gray Family

In 1926 my father had part of the farm bordering the Esplanade surveyed for 21 building blocks. The subdivision extended from the Esplanade back to Ozone Street.

William Gray, a Geelong plumber, was the first to buy, now No. 331. He built a cement garage and began the house, but the depression struck and the house was never finished. He and his wife Marion had three children - Robin, Stewart, who was my age, and Marion. We became firm friends and spent all the holidays together, swimming, rowing, playing cricket, and at night, singing as we walked along the beach. The father was a great entertainer and always had company around him. We had many jolly evenings in the "kypsy" as we called it, singing around the fire or playing games. Later, when his family had married and his wife died, Billy lived permanently in the "kipsy" until his own death. The property is still in the family.

As more people began to come to Indented Heads, my parents depended less on the farm, as they found renting cottages and hiring small boats, but still supplying milk, cream and eggs more profitable.

I was still riding my pony to school at Portarlington, determined to be a schoolteacher, but, as my parents had little money to spare, when I finished the Merit Certificate, instead of going to Geelong High School along with my classmates, Muriel Marchant and Alison Gray, I did correspondence. The Principal, Alfred Bock, helped me and encouraged me to finish Leaving and Leaving Honors, now Matriculation, at the Geelong High School.

I didn't achieve academic fame, but in sport I was Senior Athletics Champion for 3 years, winning the "Rita Bate" Cup.

In 1938, after waiting until the end of March for the schools to re-open after the Polio epidemic, I started at Queenscliff State School, as a Junior Teacher under Mr. Prichard, Principal, and Hetta Murray, Infant Mistress.

[From the files of the Bellarine Historical Society]